Cathodic protection is one of those topics that brings out the worst in boaters as too many think they have the absolute truth and few of them agree on it. The truth seems to be vague because of the number of variables. Fresh or salt or brackish water. Steel, aluminum, wood, or fiberglass hull. Aluminum outdrive, or stainless and bronze drive. And an apparent big one: anchoring out or in a marina. Shore power or not, what is docked around you, and how bad are the stray currents.

A boat the size of Seeker needs 12 to 14 zincs that are about 24 pounds each and measure 1.25 x 6 x 14 inches. The alternative is aluminum anodes. Finding scrap aluminum to make anodes is cheap and easy but to work correctly they need about 4% zinc mixed into the aluminum. But old zincs are easy to find along the waterfront too, so we decided to see if we can make our own.

Resources: Aluminum Anodes Aluminum Anode Compositions turned up from our viewers along with the confirmation from Cody that his Canadian Coast Guard vessel is using Aluminum anodes with 4% zinc.

You also get to choose if you want to weld them on or bolt them on. I really like the idea of welding them on as their is no doubt about the connection to the hull, but bolting is reported as reliable so I’m going to give way on this one. I like the idea of painting the bolt hole so that portion of the anode remains solid and prevents the connection at the base and at the nut and washer from prematurely loosening.

You also get to choose if you want to weld them on or bolt them on. I really like the idea of welding them on as their is no doubt about the connection to the hull, but bolting is reported as reliable so I’m going to give way on this one. I like the idea of painting the bolt hole so that portion of the anode remains solid and prevents the connection at the base and at the nut and washer from prematurely loosening.

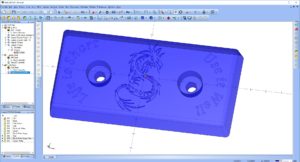

So we copied a commonly available design that is about 1.5″ x 6 x 12 and bolts on to 1/2″ stainless steel bolts welded to the hull on 6″ centers.

This will also let us practice open mold casting.

In addition to anodes the other apparently important devise is a grounding brush that connects the rotation propeller shaft inside the hull to the hull where an anode is located on the outside. “Shaft grounding is just some spring loaded brushes running on the shaft. Heavy cable to the hull. If you wanna reduce wear on the shaft you can clamp on a band around it.” –Cody

In addition to anodes the other apparently important devise is a grounding brush that connects the rotation propeller shaft inside the hull to the hull where an anode is located on the outside. “Shaft grounding is just some spring loaded brushes running on the shaft. Heavy cable to the hull. If you wanna reduce wear on the shaft you can clamp on a band around it.” –Cody